Trial evidence can take many forms. Expert testimony. Eyewitness accounts. Documents and photos. Maybe even the occasional surveillance video. In light of the recent impeachment trial of Former President Donald J. Trump, it appears we may be entering a new era in the way cases are made and defended.

The video highlight reel.

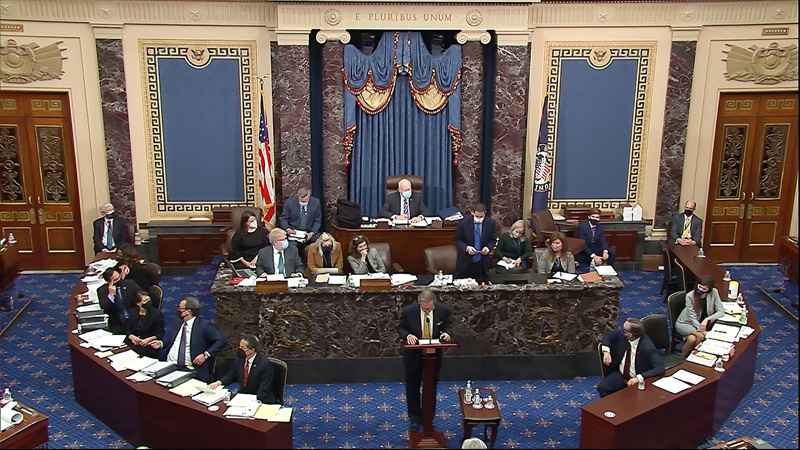

Last week, both sides made extensive use of video clips to make their respective cases. In the days leading up to the trial, much was made about never-before-seen footage from inside the Capitol that would further the prosecution’s case. Congressional leaders used video moments taken during the insurrection of the Capitol alongside video clips of the speech the president was making on the Ellipse outside the White House that same day. In doing so, the prosecution used different types of video footage to provide context to the days and hours leading up to—and immediately following—the events of January 6.

Not to be outdone, the defense had its own clip montage prepared.

Attorneys for Former President Trump showed highlights of various Democratic political figures using the word “fight” at events and in TV appearances in an attempt to demonstrate that the same rhetoric was being used on both sides of the aisle. Even news media weren’t exempt from inclusion in this (by many accounts) overly long compilation. Just ask CNN’s Chris Cuomo.

But so what? Based on the vote counts, it’s easy to dismiss the whole thing as political theater. Why does the reliance on video clips during the trial matter?

The answer is two-fold. Belief and context.

Seeing is Believing, Right?

We believe what we see. More than that, we rely on creating shared truths from the things we can see, document, and share with others. The widespread accessibility of video means we can share more moments with more people than at any other time in human history.

Without video proof, we wouldn’t get to collectively experience the joy of a child seeing his mother or father coming home from deployment. Or the terror of the first plane hitting the Twin Towers. And we certainly wouldn’t know that a police officer held his knee on George Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds.

Video gives us all the ability to see the moments we would otherwise miss.

But…(you knew there was a but coming, didn’t you?)

Just because we see the same thing, doesn’t mean we walk away with the same conclusions. While there is truth in the notion of believing what we see, it’s equally true that we see what we believe. Humans are naturally predisposed to confirmation bias. We give more weight to pieces of evidence that prove what we already believe to be true, regardless of whether it’s actually true. And this also pushes us to discard new evidence that flies in the face of our existing beliefs, particularly when emotionally charged issues are at hand.

Which is precisely what Trump’s defense was relying on. That they could use video to tap into the inherent biases of enough of the Senate to get an acquittal. Their video didn’t have to convince so much as it just had to further prove what their intended audience already believed.

Content Isn’t King. Context Is.

This all begs the question - what’s the point of video proof? If we all just seek out our own echo chambers and bend evidence to match our existing beliefs, is visual storytelling equal to shouting into the ether?

Not when video clips are layered with other forms of coverage to create deep context. The footage of the siege on the Capitol could mean any number of things. That is, until it’s contextualized with tweets and statements from the president. And correlated with the timing of statements made leading up to and throughout the day of the insurrection.

But all is in the eye of the beholder. Trump’s defense accused the prosecution of manipulating the various layers of information used to create context around the events of January 6. And then showed a lengthy reel of so-called evidence that was purposefully light on context to essentially demonstrate that — since everyone is a guilty party—no one can actually be found guilty.

And that’s the duality of video moments. They can be used to both enhance and hinder understanding. But either way, video clips are the new shared language and how they’re placed in context becomes the most impactful part of an argument.

As our communications continue to become both more visual and more bite-sized, one’s ability to effortlessly thread video highlights into the discussion will become essential. This is true whether you’re trying to win a debate on Twitter or you’re trying to convict or acquit the (formerly) most powerful person in the world.